ACHMAD Zaeni is very familiar with the sound of dirt and coral falling from a cliff near the grave of Sheikh Syarif Ainun Naim—son of Sheikh Maulana Ishaq, a religious scholar of the Samudera Pasai Sultanate—on top of a hill at Tolop Kecil Island in the Belakang Padang subdistrict, City of Batam, Riau Islands. The cliff, which is being eaten away through abrasion, is just a meter away from the wall of the tomb of that propagator of Islam in the Riau Islands. “The land continues to fall down. The last time it crumbled was a few months ago,” said Zaeni on Wednesday, March 2, pointing to a cliff and a fallen withered tree.

The 66 years-old man has been in charge of that gravesite for six years. Many people visit the place during weekends. He does not know if the abrasion at Tolop Kecil Island is caused by the current climate crisis. All he knows is that the bashing of the waves cuts away at the cliff on that hill. Large waves are also created by cargo ships which pass near the island. Strong winds from the north and heavy rains exacerbate the abrasion which occurs each year.

The one-hectare Tolop Kecil Island is not the only place being affected by abrasion. According to Yudi Admaji, the Subdistrict Head of Belakang Padang, of the 166 small islands in the area, some have experienced severe abrasions, like on the Dangka, Catur, and Suba islands. “However, Tolop Kecil Island needs to be handled quickly,” said Yudi. He estimates that the island loses about two to four meters of land annually. “A year ago we planted mangrove trees at the cliff, and now the cliff has shifted two to four meters away from those trees,” he said.

Tolop Kecil Island needs to be prioritized, according to Yudi, because it is a border area with Singapore. In Belakang Padang, Yudi added, three islands, namely Nipa, Batu Berhenti, and Pelampong, have been named outermost islands by the National Island Management Agency. He hopes that the government does not only pay attention to those islands, but also to small islands in danger of disappearing due to abrasion. “Those islands are border markers as well as state assets and tourism destinations,” he said.

Putri Island, another outermost island facing Singapore in the Nongsa subdistrict, City of Batam, is also facing extreme abrasion and once went underwater during a high tide. Yurna, a local resident, still recalls this, despite forgetting which year it happened. All six hectares of the island, said Yurna, went underwater. This also happened in 2016. “The water reached above this,” said Yurna, pointing to the wall of his house in the middle of the island.

Fitriyeni, who has lived there since 1970, said that Putri Island has now become three island clusters. “I think that (the width) of the island’s coast has shrunk by about 20 meters,” said the woman familiarly known as Upik. Researcher Nineu Yayu Geurhaneu from the Center for Marine Geology Research and Development Center, in the Indonesian Marine Geology Journal in November 2016, supported Upik’s estimate. Through analysis of satellite data from 2000 to 2016, Nineu found that abrasion had reduced Putri Island from 31,374 square meters to 24,266 square meters.

Abrasion continues even though the Sumatra regional river center of the ministry of public works and people’s housing has built breakwaters and shored up the island’s beaches, which are tourist destinations. Large waves driven by winds from the north and west damaged a levee built five years ago. “In early 2020 the waves breached the levee,” said Safrudin, a local resident.

Land reclamation of Putri Island has not gone as well as it has on Nipa Island. According to Yudi, in 2003 the central government immediately began reclaiming land on the island located in the Singapore Strait after learning about the potential of losing it due to abrasion. Today, the island is home to a border base of the Indonesian Navy. “Nipa, Pelampong, and Batu Berhenti islands have been reclaimed. The abrasion is not as bad on those three islands,” said Yudi.

Abrasion of Nipa Island has also drawn the attention of Noir Primadona Purba, a lecturer and researcher from the Faculty of Fisheries and Marine Science at Padjadjaran University, Bandung, West Java. With colleagues Muhamad Maulana Rahmadi and Ibnu Faizal, he has been observing Nipa Island’s coastline, which has continued to recede since 2011. They found seawater ate away 3,409 square meters of Nipa Island annually from 1993 to 2009. “We do not yet know the cause of this. There is a good chance it is due to a rise in sea level,” said Noir on February 20.

The team also studied conditions on 19 small islands of 111 of the outermost islands in 2021 by using 20 years of data from the Landsat 7, Landsat 8, and Sentinel 2 satellites. The goal of this research was to see how vulnerable small islands are to the climate crisis.

This research indicated that, on average, the rate of area loss of those small islands was 5.08459 percent, with most islands being at an intermediate vulnerability level. “The vulnerability was low to intermediate. None were high,” said Muhamad Maulana Rahmadi. The one island which was at a critical level of vulnerability was Iyu Kecil Island in the Malacca Strait, Karimun Regency, Riau Islands. The area of this island had decreased by 32.13774 percent (0.008733 square kilometers) over 19 years.

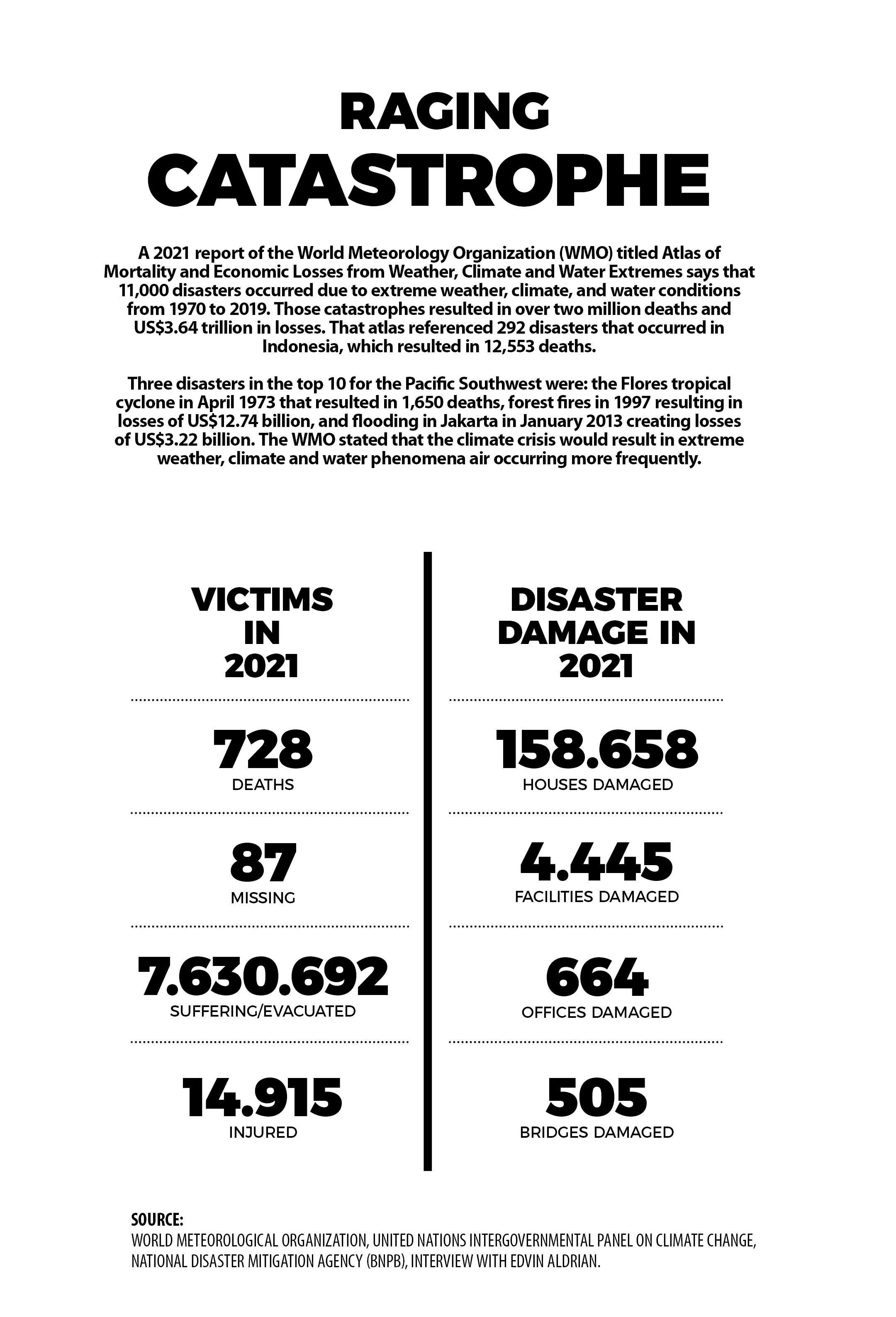

ABRASION and tidal waves are hydrometeorological disasters, as are flooding, cyclones, high winds and landslides. According to Abdul Muhari, Head of the National Disaster Mitigation Agency’s (BNPB) Center for Data, Information and Disaster Communication, the number of natural disasters has continued to increase over the years. “It is dominated by wet hydrometeorological disasters,” said Abdul Muhari in a WhatsApp message on March 17.

According to BNPB data, in 2021 there were 5,402 natural disasters that occurred in Indonesia. For hydrometeorological disasters, there were 1,794 floods, 1,577 tornadoes and tropical cyclones, 1,321 landslides, and 91 instances of storm surges and abrasion. Abdul Muhari explained that each incident or natural phenomenon is recorded as a disaster if it results in deaths or material losses. “If not, it is considered a natural phenomenon,” he said.

It is possible that there are other small islands which are experiencing abrasion and being submerged but are not in the BNPB’s disaster database because they are uninhabited or not yet recorded. According to Antam Novambar, Secretary-General of the Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, it is difficult to say how many small islands have been lost. “Of the 17,504 islands in Indonesia, only 16,771 are on record at the United Nations and in the Gazeter Republik Indonesia 2020. The rest are still in the identification process,” said Antam in a written reply.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) considers small islands important enough to have their own chapter in a report released on Monday, February 28, in the second part of their Sixth Assessment Report. In a report titled Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability, the IPCC strongly believes research that found small islands are becoming more affected by rising temperatures, tropical cyclones, storm surges, droughts, changing rainfall levels, and rising sea levels.

The IPCC sees those phenomena as being significant because a great part of the world’s population, economic activity, and important infrastructure are concentrated near water. Nearly 11 percent of the global population or about 896 million people live in low-elevation coastal areas which have the direct potential to experience disasters such as abrasion, tidal waves and flash flooding.

As an archipelagic nation where a majority of the islands are small (about 13,000), Indonesia has a vested interest in this IPCC report. Researcher Heri Andreas from the Geodesic Team of the Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB) found 112 cities and regencies which are in danger of losing coastline. Fifty locations, such as Probolinggo (East Java), Pekalongan (Central Java), North Tangerang (Banten), Muaragembong-Bekasi (West Java), Subang (West Java), Indramayu (West Java), Kubu Raya (West Kalimantan), Katingan (Central Kalimantan), Meranti (Riau), Siak (Riau), and Dumai (Riau), are having trouble with flash flooding. “Pasir Jaya village in Muaragembong is now a kilometer out to sea. Seni village in Demak (Central Java) has already moved two kilometer out to sea, while Semut village (Central Java) has disappeared,” he said.

OF the 17,504 islands in Indonesia, over 13,000 are small islands (with an area of about 2,000 square kilometers). Muhammad Maulana Rahmadi, a researcher at Noir Primadona Purba, and Ibnu Faizal from the Faculty of Fisheries and Maritime Science of Padjadjaran University, Bandung, found that rising sea levels has reduced the land area of the 19 outermost islands by an average 5.0845 percent.

In Sumatra, seawater can inundate 5 to 10 kilometers of land because the beaches are very flat and there are no hills. According to Heri, the contribution of a rising sea level to flash flooding is believed to be small. It rises about six millimeters to one centimeter per year. Meanwhile, the land is subsiding 10 to 20 centimeters per year. “That is what is causing the massive flash flooding,” said Heri. That land could be sinking due to aggressive pumping of groundwater or the activity of old oil wells.

Edvin Aldrian, Deputy Chairman of the IPCC Working Group I, said that the report made by the Working Group II focused on the impacts, adaptation and vulnerabilities of climate change. Adaptation, according to him, means that climate change has occurred and cannot be turned back. “For instance when a rise in sea level has already resulted in inundating a beach. So we adapt by raising houses, building stilt houses, planting mangrove trees, or building sea walls,” he said.

However, the researchers—in that 3,675-page report—pointed out that adaptation programs should not be counterproductive or maladaptive. “For example, sacrificing a mangrove forest or coral reef to build a breakwater,” said Edvin. “Good adaptive action is like planting mangroves or protecting the coastal ecosystem.” Another concern, said Edvin, is that adaptive action could be too late, as it is done when the environment can no longer be restored.

Tata Mustasya, Coordinator for the Climate and Energy Campaign of Greenpeace Southeast Asia, said that the climate change adaptation program must focus on helping vulnerable groups, namely women, children, the elderly, people with disabilities, and the impoverished. So that there are funds for adapting, he said, “Advanced countries must make commitments to pay for losses and damage caused by the climate crisis.”

VARIOUS indications of climate change have had negative impacts on the economy of communities and state. Rice farmers in various regions, for example, have recently experienced more frequent crop failures, or poor yields. That was why in 2013, the government and the House of Representatives passed Law No. 19 on the protection and empowerment of farmers which became the basis for the establishment of the Rice Farming Business Insurance (AUTP).

This insurance provides compensation for losses due to crop damage so that farmers could get their production costs back. But that did not really solve their predicament. “(Under the AUTP) maximum coverage is just Rp6 million per hectare. Meanwhile, production costs are Rp12-15 million per hectare,” said Syamsudin, a farmer in Pakisjaya, Karawang Regency, West Java.

Climate change also causes coastlines in some regions to move further to residential areas. For example, in Sayung subdistrict, Demak, one of the hamlets, Timbulsloko, is practically situated above the seawater. A total of 155 families in the hamlet had to raise the floor of their houses up and closer to the roof in order to be safe from tidal flooding. At least 15 families chose to leave the hamlet. “I’m holding on because most of my relatives live here,” said Sonhaji, head of the local neighborhood unit, on Friday, March 4. Since 2015, the local government and residents have been promoting mangrove planting to battle abrasion and rising waves but to no avail. Each time, the ocean currents swept away almost all the seedlings that were planted.

In South Kalimantan, forest use concessions and illegal logging in the Meratus Mountains are suspected to be the cause of the massive flooding that submerged 102,340 houses in 11 regencies and cities in that province on January 12 last year. “That was caused by damage at the water catchment areas and areas along the river,” said Dwi Putra Kurniawan, Head of South Kalimantan’s Indonesian Farmer Union (SPI), on March 23

Last year, the Ministry of National Development Planning/National Development Planning Agency (Bappenas) studied the potential economic losses stemming from climate change. They found that without policy interventions, various disasters related to climate change could cause economic losses up to Rp544 trillion in 2020 to 2024. The sectors predicted to be hit hardest are coastal and marine with potential losses of Rp408 trillion, agriculture is about Rp78 trillion, the waters sector Rp28 trillion, and the health sector Rp31 trillion.

The government allocated Rp307.94 trillion of climate change funds from 2018 to 2020, an average of roughly 4.3 percent of the annual State Budget. Even so, the annual amount of the funds continued to decline. In 2018 the budget for government institutions and ministries for climate change was Rp132.4 trillion, it decreased to Rp97.66 trillion in 2019, and decreased further to Rp77.81 trillion in 2020. Last year the climate change budget rose slightly to about Rp86.7 trillion.

However, efforts to mitigate climate change are still far from sufficient. Based on Indonesia’s 2018 Biennial Update to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), US$247.2 billion (about Rp3,461 trillion) is needed up to 2030 to dampen the impacts of climate change. Finance Minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati verified this. “This means that at least Rp266.2 trillion in resources is needed each year,” she said in a Climate Change Challenge discussion at the University of Indonesia on June 11, 2021.

That Rp266.2 trillion, Sri added, is more than the 2021 health budget of Rp170 trillion. “For that reason, efforts to mitigate the impact of climate change must be done through mutual assistance between the government, private sector, philanthropic efforts, and the public,” she said.

Project Lead

Writers

Contributors

Multimedia

Translator

Editor